Character dimension is a concept I’ve found very useful when striving for more appealing character designs. I’m not talking about literal dimension of forms, but how to give the characters the appropriate amount of personality and interest relative to their screen time in the story. There are a lot of theories on this, so I’m picking the pieces from those theories that best apply to character design.

This idea of character dimension is best explained with contrast. There are four different levels of dimension as it relates to visual design, with the highest level being a three-dimensional character.

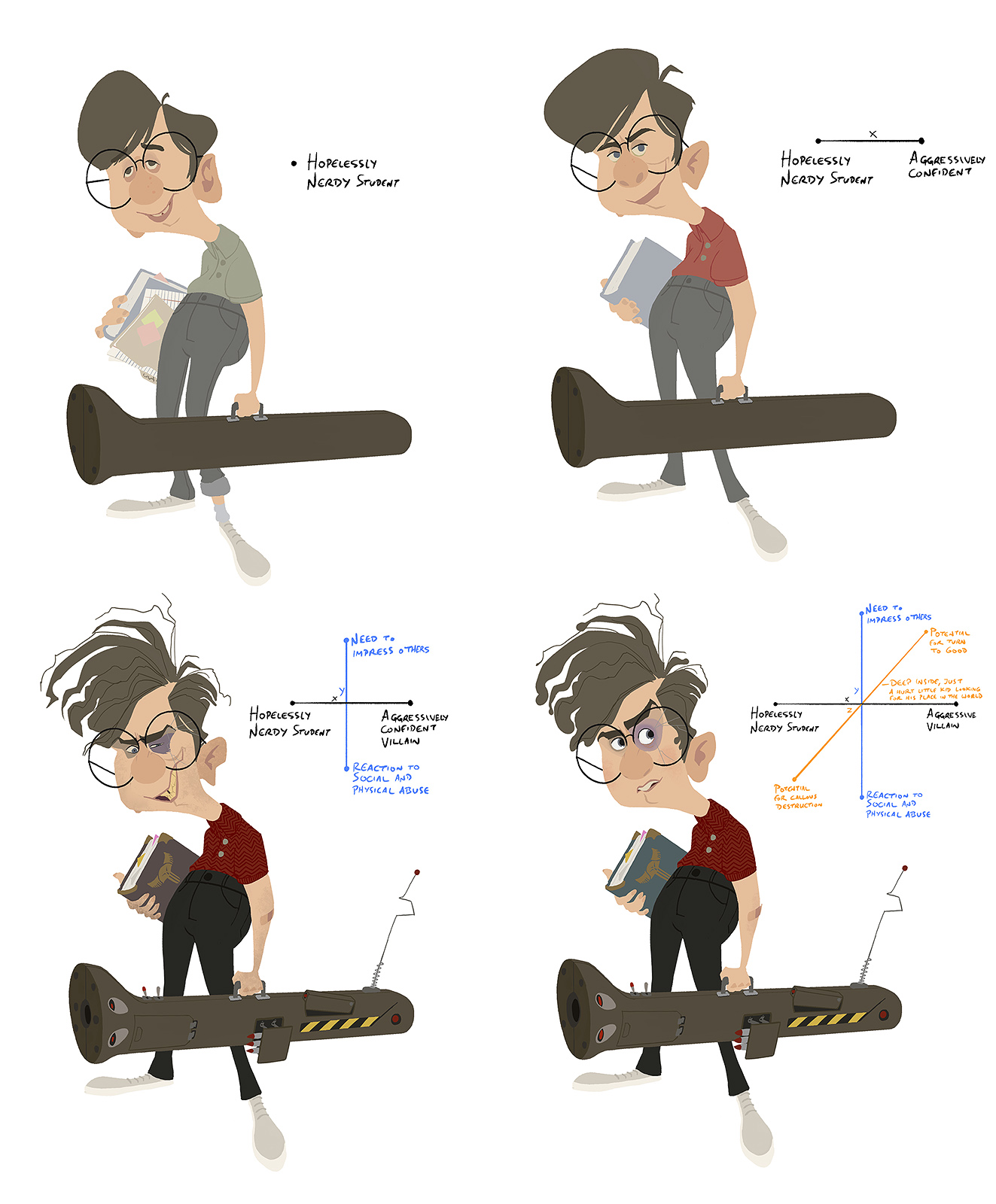

The first level of depth is a “bit” character. Think of a bit as a single point in space, with no dimension. A bit character displays only one character attribute—usually meant to fulfill a single purpose as that character stands in the spotlight onscreen for a very brief time. Here’s an example of a bit part: the hopelessly nerdy character.

To keep this character aligned with that bit part, I tried to make everything on him give a “sad sack” feeling—droopy, soft, and ineffective. This character is understood in his entirety almost immediately, which makes him useful for brief moments with no introduction. A character like this can still act against type in that instant, but that action must be understood quickly in context of that simple and clear character bit, or the contrasting attributes will only create confusion. The weakness of a bit character is that after this character serves his momentary purpose, he will become insufficiently interesting* for extra time in the spotlight.

(*As a side note, I should mention that any character design can be enriched through great writing and animation. Appealing and appropriate characters can make great writing and animation better, but even the best character design will struggle without the other two.)

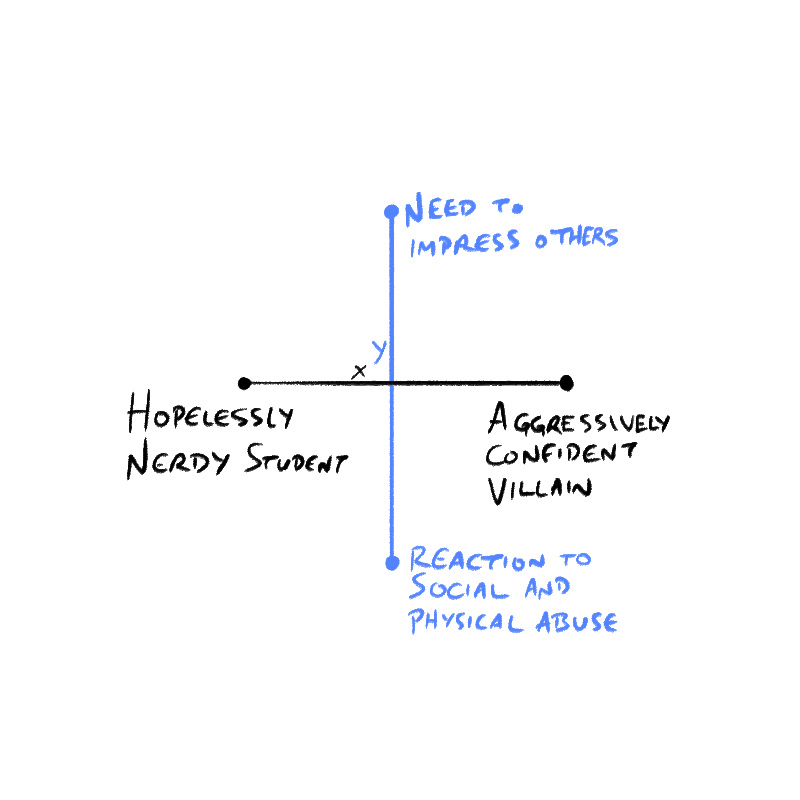

Imagine taking that single point in space, that surface character attribute, and stretching it into a line. Now you have two poles possible with contrasting components, or a one-dimensional character. The contrasting attributes here are different from a bit character acting against type, because this character may be seen at varying points along that line throughout the film (while a bit character acting against type will always act the same). My example of a one-dimensional character adds aggressive confidence to a hopelessly nerdy character.

I communicated the two poles of this character’s single dimension by contrasting gesture, expression, and shape language against his easily understood role or type. You can also do this with contrasting costume decisions, color scheme, and other elements. Usually, the one-dimensional character is defined by “what,” meaning both poles are expressions of how that character fills his role in the world. One-dimensional characters remain interesting for longer, and they can even have simple character arcs, but they lack any real depth.

Adding one more dimension to a character creates depth and a lot more interest. This second dimension is usually defined by “why?”, or the character’s history and motivations. Expanding on the example character, who now has one dimension that goes between hopelessly nerdy all the way to confident villain, but also adds a second dimension that shows a little bit of the inner demons driving him; a life of bullying and misfortune.

In this case I imagined the opposing poles of his second dimension are his need to be someone—to have power over his life, contrasted with his complete helplessness in the context of the strength and socially-driven world he has always lived in. I used recent fight-related injuries and the expression to suggest the character’s history and the hardening of his motivations. Typically, the visual language for history and motivation is going to be a second read, meaning that the first dimension is the first stuff the audience sees, but is then modified with a closer look at the character. A character with this much complexity needs enough screen time to show all combinations of the four extremes of these two dimensions; otherwise he collapses down to a one-dimensional character in the story, in which case the audience will feel dissatisfaction and an intuitive need to know more about him than his screen time allows, because of the amount of conflict the character suggests. That said, even if I’m designing a one-dimesional character, I will often explore the second dimension story-wise because understanding the backstory and inner demons can suggest interesting expressions of that single dimension that I wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

The third dimension is the “who” of the character; and it is the hardest one to quantify in the visual parts of the character design. This dimension demands a lot of screen time, as the character now needs to go through the hero’s journey. A protagonist, the love interest, a sidekick, or even the main villain can be three-dimensional, so long as there’s enough time to unravel all three dimensions.

This character starts the story being defined by WHAT he is (the hopelessly nerdy kid bordering on supervillainny), then the story would explore WHY he has become that way (inner demons of social and physical abuse by peers he wants to impress), but to gain the third dimension, then the story must test the limits of that character beyond the surface attributes and internal desires or motivations. In other words, you can’t know WHO this character is until you have seen the things that outwardly define him stripped away, and see the choices he makes when facing the resulting desolation of his failure. In visual design terms, you cannot show this journey all at once! But you can show the potential for that character to change. More nuance in shape language, a little baby face bias, more thoughtful, vulnerable eyes, and even a less “set” demeanor can help cue the audience that this character is not yet done with his journey. Unlike previous dimensions, you can sometimes apply three-dimensional design to a character in a two-dimensional role without frustrating the audience; so long as the suggestion of potential-for-change doesn’t compete with the role the character plays in the story.

Is it possible to have a character with more dimensions than this? Yes; even four and five-dimensional characters can work in a story, but fitting that extra information into a design is very difficult! My experience is that the first and second dimensions can be layered into a character after the initial design, so your design process doesn’t need to include all this information from the start, so long as you can get your art director to be patient with the exploration of those dimensions. Character dimension is less about which is good, better, or best; and more about designing characters that are appropriate for their roles in the story. I hope this proves to be a helpful tool to other aspiring character designers out there!