Color Schemes

Though the accomplished author who made fun of me in the comments for using a real word was joking, I thought I ought to do a post on triadic color schemes.

Since James Gurney has already covered this subject in great detail, rather than cover the basics again, I'll just add a few thoughts to the discussion.

Many color schemes work just as well whether you are using the traditional color wheel (ROYGBIV) or the color wheel of light (RBG). While the ROYGBIV wheel stretches the warm end of the spectrum, making the wheel a little more polar in its temperature, red and cyan resonate against each other as complements just as well as, and possibly more strongly than, red and green. Same is true for magenta and green, yellow and blue (which is closer to indigo on most monitors), and so forth.

However, triadic color schemes---images using three equidistant colors from the color wheel---don't act the same in both wheels. This is probably because of the stretching I talked about above.

The advantage to a traditional triadic color scheme is that its even nature comes across in images using it. It's not an exciting color combination, but the even and predictable nature of it makes it comfortable, almost friendly.

A triadic scheme from the RGB spectrum still works fine if you are just looking for interesting color combinations. But for some reason it doesn't achieve the same effect as the ROYGBIV version.

This may not be a surprising discovery to some, but I've noticed that the farther you push a color scheme away from peak saturation and value, the more you lose the strengths of that color scheme. However, the colors still retain a shadow of what they used to be, so even at its extremes a color scheme has a hint of the message that goes along with it.

While a triadic color scheme can feel balanced, safe, and even child-like, which triad you pick for your subject matter can still strongly affect the mood of your image. Look at the difference that happens by shifting just a little in one direction:

See how much more off-putting and aggressive the character appears in the second one?

Don't expect too much from a color scheme, though, because the color scheme is often one of the weakest factors in communicating the emotional tone of an image. If I were to assign a priority to the effectiveness of a design element in establishing the theme, emotion, or message of an image, I'd place the priorities something like this:

(Most effective)

1. Style

2. Subject matter/content (I would include shape language here)

3. Lighting scheme

4. Value/color composition

5. Surfaces/Textures

6. Color scheme

(Least effective)

These all might switch places depending on the image, but the point is, don't count on a color scheme to solve your problems if your drawing, lighting, etc. aren't saying what they're supposed to.

So think of color schemes as modifiers: A friendly color scheme won't fundamentally change how you feel about an image, but it might layer in subtext or cast something unexpected into the tone of an image.

Since James Gurney has already covered this subject in great detail, rather than cover the basics again, I'll just add a few thoughts to the discussion.

However, triadic color schemes---images using three equidistant colors from the color wheel---don't act the same in both wheels. This is probably because of the stretching I talked about above.

The advantage to a traditional triadic color scheme is that its even nature comes across in images using it. It's not an exciting color combination, but the even and predictable nature of it makes it comfortable, almost friendly.

A triadic scheme from the RGB spectrum still works fine if you are just looking for interesting color combinations. But for some reason it doesn't achieve the same effect as the ROYGBIV version.

This may not be a surprising discovery to some, but I've noticed that the farther you push a color scheme away from peak saturation and value, the more you lose the strengths of that color scheme. However, the colors still retain a shadow of what they used to be, so even at its extremes a color scheme has a hint of the message that goes along with it.

While a triadic color scheme can feel balanced, safe, and even child-like, which triad you pick for your subject matter can still strongly affect the mood of your image. Look at the difference that happens by shifting just a little in one direction:

See how much more off-putting and aggressive the character appears in the second one?

Don't expect too much from a color scheme, though, because the color scheme is often one of the weakest factors in communicating the emotional tone of an image. If I were to assign a priority to the effectiveness of a design element in establishing the theme, emotion, or message of an image, I'd place the priorities something like this:

(Most effective)

1. Style

2. Subject matter/content (I would include shape language here)

3. Lighting scheme

4. Value/color composition

5. Surfaces/Textures

6. Color scheme

(Least effective)

These all might switch places depending on the image, but the point is, don't count on a color scheme to solve your problems if your drawing, lighting, etc. aren't saying what they're supposed to.

|

| If anything, the primary colors make him seem even more freaky |

Chameleon

Rhino God

The Uncanny Valley

Most people have heard of "The Uncanny Valley" by now. I've heard people refer to it in two contexts in the animation industry: characters that are almost lifelike but are just enough off to be creepy, and stylized/cartoon characters who have an off-putting amount of realistic detail. I want to talk a little about the second one because I've run into it more often recently when artists have asked me for critiques.

I don't think there is a hard and fast rule for this type of uncanny valley. When I watched The Adventures of Tintin, at first I was really bothered by the cartoon characters with realistic eyes and hands. But by the end of the film I was engaged enough in the story that I didn't notice so much anymore. I suspect that a lot of our reaction to the uncanny valley is a bias that can be broken down with repeated exposure.

However, until the kids who prefer a Robert Zemeckis zombie-fest become the norm, artists who want to add realism into the animation industry are going to have to be sensitive to the issue. Most audiences like detail and realism, so there's nothing wrong with trying to push things that way. But how far can you go before you start alienating people?

For a character with cartoon proportions, the complexity of the forms and surface details are both factors.

In my experience, the most important form details for navigating the the uncanny valley seem to be the eyes and the nose. Make the eyelids too defined, and the character will fall apart. Visible skeletal structure on the hands and feet are a good target for abstraction as well. Realistic forms on the ears and lips might be distracting, but don't seem to "break" the character in the same way as the other features.

Does this mean you can never define the forms around the nose? Not necessarily. A good rule of thumb is to ask, "Do I want people to stare at this feature?" Because people's eyes will be drawn to any unusually detailed part of a stylized character. If the part they are staring at informs them about the character, then that can be a good thing. But if the nostrils aren't particularly important, then your design might be better off without them or at least without some of the structures surrounding them.

Even if you keep the forms simple, the texture on those forms can make a character disturbing. Skin pores, tissue striations, and loose hairs can be particularly offensive (in this case intended for humor):

http://pixeloo.blogspot.com/2008/03/super-real-mario-world.html Finding a more abstract version of these textures can still give you high detail without sacrificing appeal:

Of course, some of you might look at my three examples above and think that the third version is just fine, while others might feel that the middle version is already descending into the uncanny valley. What is okay depends on your audience and what you're trying to say with the style (grotesque is sometimes good).

I don't think there is a hard and fast rule for this type of uncanny valley. When I watched The Adventures of Tintin, at first I was really bothered by the cartoon characters with realistic eyes and hands. But by the end of the film I was engaged enough in the story that I didn't notice so much anymore. I suspect that a lot of our reaction to the uncanny valley is a bias that can be broken down with repeated exposure.

|

| These guys' eyes still freak me out |

|

| Safely abstracted |

|

| ??? |

|

| Uncanny Valley |

In my experience, the most important form details for navigating the the uncanny valley seem to be the eyes and the nose. Make the eyelids too defined, and the character will fall apart. Visible skeletal structure on the hands and feet are a good target for abstraction as well. Realistic forms on the ears and lips might be distracting, but don't seem to "break" the character in the same way as the other features.

Does this mean you can never define the forms around the nose? Not necessarily. A good rule of thumb is to ask, "Do I want people to stare at this feature?" Because people's eyes will be drawn to any unusually detailed part of a stylized character. If the part they are staring at informs them about the character, then that can be a good thing. But if the nostrils aren't particularly important, then your design might be better off without them or at least without some of the structures surrounding them.

Even if you keep the forms simple, the texture on those forms can make a character disturbing. Skin pores, tissue striations, and loose hairs can be particularly offensive (in this case intended for humor):

http://pixeloo.blogspot.com/2008/03/super-real-mario-world.html Finding a more abstract version of these textures can still give you high detail without sacrificing appeal:

Of course, some of you might look at my three examples above and think that the third version is just fine, while others might feel that the middle version is already descending into the uncanny valley. What is okay depends on your audience and what you're trying to say with the style (grotesque is sometimes good).

Griffgar the Terrible

Comic-Con Demo

Influence map

I've seen these around before but never tried it because I didn't realize how useful and interesting an exercise it would be.

I agonized over who to leave out, and I still wonder if I should have included artists such as Dave McClellan, Joe Olson, Erwin Madrid, Marcelo Vignali, Paul Lasaine, and Paul Felix. Those artists deserve credit in my development but I just ran out of space.

I just have to add that Alan Tew basically taught me how to draw and I owe him more than I have room on this sheet for. Whether he takes that as a compliment will depend on how he feels about my drawing ability now. :)

The most interesting part of doing this was realizing how many good artists I'm NOT influenced by. There are mobs of artists who I've thought for a long time are amazing, yet they have not in any way changed the way that I work or think. This is a really strange thing that I don't understand.

And yeah, I know Bengus isn't an artist but a group of artists. More than one of them influenced me, so I'm including them as a group.

I agonized over who to leave out, and I still wonder if I should have included artists such as Dave McClellan, Joe Olson, Erwin Madrid, Marcelo Vignali, Paul Lasaine, and Paul Felix. Those artists deserve credit in my development but I just ran out of space.

The most interesting part of doing this was realizing how many good artists I'm NOT influenced by. There are mobs of artists who I've thought for a long time are amazing, yet they have not in any way changed the way that I work or think. This is a really strange thing that I don't understand.

And yeah, I know Bengus isn't an artist but a group of artists. More than one of them influenced me, so I'm including them as a group.

Time Repairman, Progress

Neversink Tree Interior

This was one of the most difficult pieces I've ever done. The pencil version was extremely large for one of my drawings (done on 2 11x17 sheets taped together in back), and had to have enough detail to look good even when clipped out into small sections, which is how it was used in the book. I don't think I did a good job getting the values to feel good in the scan (it's supposed to read as a silhouette and the interior detail should be secondary), but the printers got it right in the book, so I guess that's what matters.

Neversink interior

Snowy Owl

Pygmy Owl

Neversink is coming out this week and I just got a bunch of copies from the publisher. It turned out really nice!

This is one of the interior spot illustrations; it turned out pretty small in the book so here's a larger look.

I'll post some more of the interior art here over the next couple of weeks, so stay tuned!

This is one of the interior spot illustrations; it turned out pretty small in the book so here's a larger look.

I'll post some more of the interior art here over the next couple of weeks, so stay tuned!

Work in Progress Environment

Air Scooter

I started this back in November, which is why it has an autumn theme. Thanks to Ben Simonsen for the helpful paint-over suggestions.

Meeting sketches

Teaching fun

One of the pleasures of teaching for Schoolism is that the school brings in people from all over the world and all levels of the art industry. Many of my students are more skilled/talented than I am, and half of them already had impressive jobs in the industry, but took the class because they wanted to fill out one corner of their expertise a bit. I love teaching, and helping anyone learn is rewarding. But it's especially fun when an artist gets exactly what you're trying to say, and pulls off something amazing or unexpected with the limited criteria of an assignment.

Here are some of the highlights from the final assignment of last semester. I gave the students line art and a lot of freedom with the lighting scheme, render style, surfaces, etc.:

|

| by Dane Madgwick |

|

| by Colin Foran |

|

| By Claire Hummel |

|

| By Stijn Van Doorselaere |

I've also had some impressive students in the self-taught class. I don't get to interact with them as often, but I still enjoy seeing what they do and how they react to the lessons. An artist named Johan Törnlund wrote a thoughtful review (with some criticism also, which is nice because now I can address those problems), here: http://feedchicken.blogspot.com/2012/01/schoolism-review.html

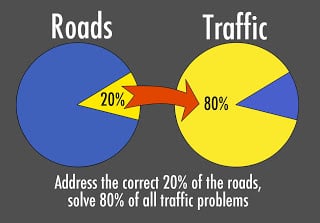

The 80/20 Rule

I've often heard artists, designers, management, etc. use "the 80/20 rule" to explain their choices.

"You want 80% to be rest areas and 20% areas of detail"

"80% of this geometry should be interactive and 20% non-interactive"

"As long as we get it 80% right, the extra 20% doesn't matter"

The problem is, none of these things have anything to do with the 80/20 rule. So let's get it right, because this is an important one if you want be a faster artist.

The 80/20 rule states that 80% of a system will be affected by 20% of the variables in it. So that 20% matters a lot. 80/20 doesn't mean that everything divides neatly into that ratio, or that that 80% should be one thing and 20% should be another. Instead, it's a principle of resource allocation.

So as an artist, what is that 20% of your process that takes 80% of your time or resources? There are multiple answers to this question. Here are some ways it applies to me:

How often do you get a painting to the point where it's looking good and you start feeling like you're just about done, only then you spend way more time finishing the painting up than you did getting it to that point? For me, this is true nearly every time. If you paint in detail or care about your brush strokes, this is just a fact of life.

But to make use of the 80/20 rule, you need to do more than identify the problematic 20%. It may be useful for setting proper expectations, but you won't get any faster to know that.

Where the 80/20 rule becomes useful in this case is by applying it in another related area. If I were to uniformly apply detail across this painting once I finished the block-in, it would have taken me three times as long. So instead, once I got to hour 3 or 4, I tried to identify the 20% of the painting that would likely demand 80% of a viewer's attention. Then I focused a disproportionate amount of time and effort developing those areas. The remaining 80% of the painting then fell naturally together in support of the high-attention areas. This is the magic of the 80/20 rule: tackle the correct 20%, and the other 80% often falls into place.

What are some ways that the 80/20 rule could be used to speed up your process?

Helper

Watercolor brushes

A comment in the previous post on brushes made me think I should examine the "Real Watercolor" brushes more closely, but with the proper expectations (ie. unexpected results are okay). So I did, and I didn't try anything too crazy with them, but I like them better in that context. Making multiple watercolor layers at once is nice. The watercolor eraser is awful, though. This was done for the Avalanche blog:

I still like the digital watercolors better though. This was a drawing session a week or two ago.